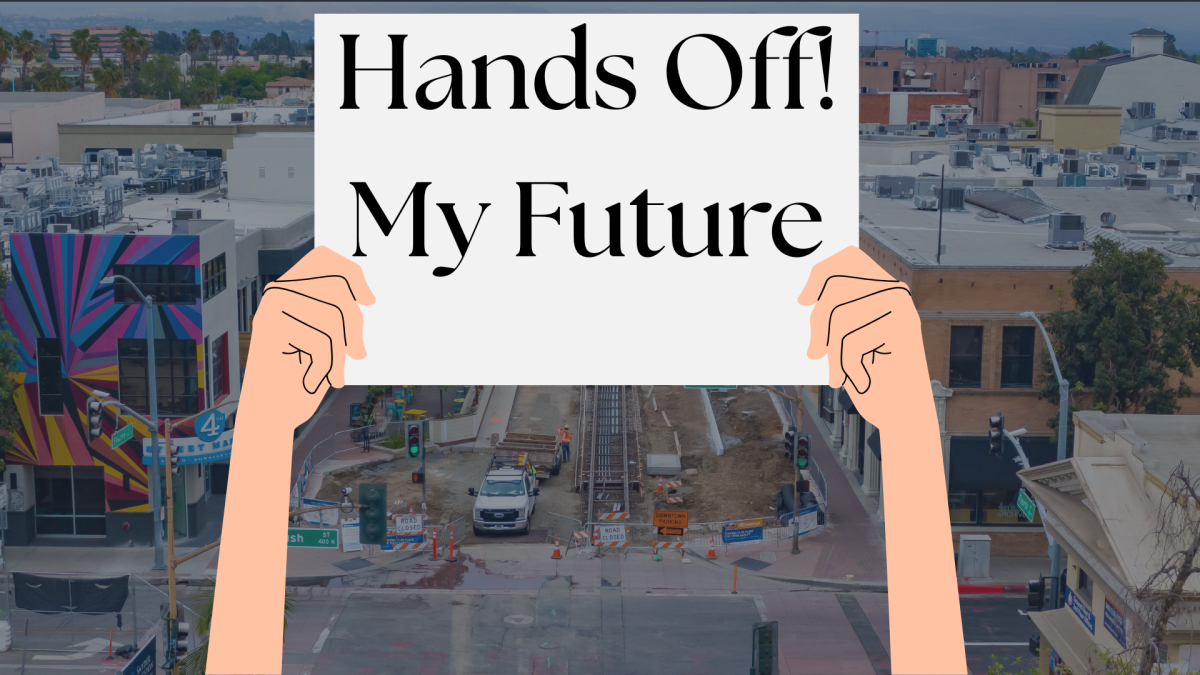

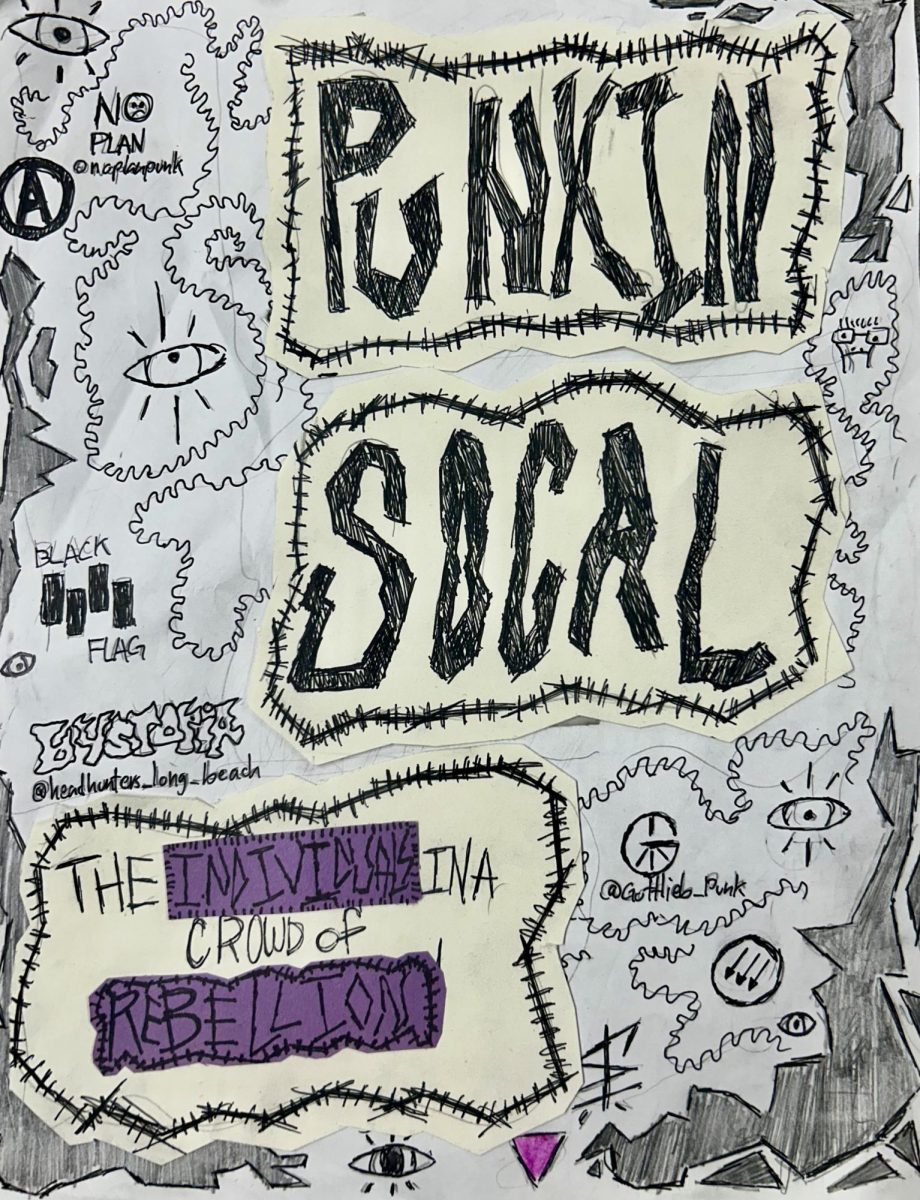

Ever since punk rock emerged in the 1970s with bands such as The Ramones in New York, The Clash in the U.K., Dead Kennedys in the Bay and Black Flag in Los Angeles, the people who have kept it alive are not only the ones on stage, but the faces in the crowd. Those who keep punk thriving rebel inside and outside of the venue. That includes here in SoCal where bands continue to form and inspire rebellion.

Punk does not take its roots from concerts or from big sponsored shows, but from the smaller venues, skate shops, warehouses and even houses. In SoCal, everywhere you look there are venues, especially in Los Angeles, which has been an epicenter of the scene for years. But a question remains: which is better, a festival where thousands of people show up to see punk-rock legends, or a small show with an up-and- coming band?

Small shows or festivals?

Guitarist for pop-punk band NoPlan, Matt Kearney shares his opinions.

“I think some of the values that are inherent to punk and hardcore, are often demonstrated at small shows,” Kearney said. “You can see DIY ethics in action where people work collectively to make an event happen.”

Kearney goes on to explain more about why he feels a more intimate venue provides a better experience, not only for the crowd, but as well for the band members themselves.

“It’s contagious, I feel like that’s one of the most special things about all this stuff; there’s no barrier to entry. If you want to do something, you can just do it,” Kearney said. “With no age restrictions, no barrier between band and audience, no corporate sponsor.”

Tattoo artist and musician, Roman O’Cadiz, shares his thoughts as well.

“There’s room for everything, I’d say these days authorities have made previous alternatives extremely difficult, and adhere more to things that promote capitalism,” O’Cadiz said.

O’Cadiz, who prefers small shows, soon after explains how he believes that there shouldn’t be a limit to what can and cannot be a venue, along with how there should not be a restriction to who is allowed to attend a show. He believes there should be many open opportunities for shows and events for anybody, no matter what, because to him, music and community is mental health.

“Punk should be free in the sense that it should be enjoyed at all types of bars, events, anywhere in all the types of ways by all kinds of people of all ages,” O’Cadiz said. “I think the government should subsidize music and allow for free festivals because music is mental health, and punk proves this.”

Bassist for defunct band, Dystopia, and now owner of HeadHunters, Todd Kiessling talks about festivals with small show energy.

“I prefer smaller underground shows, if you gotta have a big a– festival with the same atmosphere and low prices, then f— yeah that’s great, but it’s rare for that to happen, it’s very rare for that to happen,” Kiessling said.

Here Kiessling refers to the show promoters, and band promoters, who do not care about making music, instead about making a profit.

Patch & pin vendor for “The Peasants Revolt,” Jesus Vazquez shares his thoughts on festivals.

“It’s kind of ironic how all these punk bands that used to stand for anarchism, are now in a festival that’s basically a melting pot of capitalism,” Vazquez said.

Los Angeles punk

Los Angeles, and SoCal in general has a plethora of venues no matter where you go. This led to the punk community having a joke that Los Angeles Punks are spoiled with all their venues and bands; lead singer of Gottlieb, Andrew Pescara, shares his thoughts on this saying.

“There’s so many things you can see in L.A. that I think crowds tend to stick to their niche a lot more, and they have a lot more to compare you to, so it’s a lot harder to impress them,” Pescara said.

Pescara says how there isn’t anything necessarily wrong with this.

“In L.A., a mixed bill with like, a pop punk band and a power violence band is like a death sentence, no one’s gonna come see that, but outside of L.A., mixed bills are wanted to see because they’re just generally into punk,” Pescara said.

Kiessling also talks about how punks have their own scenes deeper within the subculture.

“It kind of depends on the scene and the group of people, because there’s a lot of different subgenres and a lot of different, little isolated scenes,” Kiessling said. “but I would say the underground is still thriving.”

Like Pescara, O’Cadiz talks about how he thinks that Los Angeles is a hard place for bands to get a crowd, because of how many options the people have for shows.

“We live amongst the entertainment industry so we are flooded with media culture and information and top of that, we have musical events happening almost everyday within many cities,” O’Cadiz said. “We definitely are a hub for shows. And I’d say L.A. is the toughest crowd out there for touring bands.”

Today’s scene

Kearney believes that places in the U.S. do not have their own unique sound within the punk genre any longer.

“I don’t think there are regional differences anymore. People make references to them like ‘Boston-Hardcore’ or ‘SoCal Punk,’ and those things are definitely real, identifiable things,” Kearney said. “But they haven’t really been exclusive to their regions for a long time.”

In addition, many modern punk bands are clinging to an older sound and style, and do their best to replicate it.

“I think a modern punk band is either trying to emulate something from the past, or is a product of a multitude of influences from different places and times,” Kearney said.

More than the venues, and more than the bands, the people themselves play possibly the largest role in keeping the subculture alive, and sometimes it is hard to tell who is a punk, and who is not.

“You f—– don’t judge a book by its cover, because you never know,” Kiessling said. “It’s hard to tell unless you’re inside someone’s head.”

O’Cadiz talks about why he believes that Los Angeles has been the boiling pot for punks, and why the major cities, landmarks, business and other factors play into the scene that has developed within the borders of SoCal.

“L.A. is different in that it’s L.A.; it has its own weird infrastructural geopolitical problems, and its own weird mix of people,” O’Cadiz said. “Of course Hollywood and fame/social media plays a big role in shaping some people’s objectives, but L.A. is big enough to have similarities found in other scenes like all ages spaces, DIY, and squats.”

Punk personal style

There is no dress code to punk, there is no code to punk in any sense, and we should not take to dividing ourselves. Vazquez believes this as well, and wishes that anybody who wants to get into the scene should feel comfortable knowing they won’t be judged.

“Don’t be afraid to express yourself, be it by your looks, your ideals, your art, your god-damn bodily stink, by any means necessary,” Vazquez said. “I believe the punk scene should be about brotherly love and care for one another. Inclusion is the word I’m looking for.”

Pescara also shares his experiences about when the band he sings for, Gottlieb, first played, and how a lot of the people they opened to were young kids half the age of Pescara.

“We kind of debuted to kids half our age. I’m 28 you know, yeah, and I think they liked us because that scene has a very specific and a very cool sound,” Pescara said.

Benefit and fundraiser events

A lot of punk revolves around community; this includes benefit shows, and fundraisers, which is what Kiessling’s store relies on. However, some bands take pride in making music that is meant to be moshed and fought to, which when mixed with a show when money is meant to be raised, can cause issues. Pescara thinks about what can happen when these two mix.

“I’ve seen people throw benefit concerts where 5000 people show up and they’re supposed to be raising money for charity, and those 5000 people will destroy a public park and a library,” Pescara said, “and the gains that they have in terms of donations is like five cans of beans.”

O’Cadiz gives his opinion on how a benefit show can help, and inspire others to donate to charities, however, similarly there are many issues with hosting a charity show.

“Humans do get sick with power, and even ‘punks’ do, I’ve witnessed countless money fraud within movements,” O’Cadiz said. “But I will say that I have seen a lot of fundraisers that are legit and honest, and I do find them very inspirational because they open space for bigger dialog.”

Vazquez, who attends shows regularly as a vendor, talks about how comforting it is to see a benefit show that actually succeeds in bringing people together.

“It’s good to see a community of stinky degenerates coming together and helping one another. Being utterly human and kind, giving anything they can to people they might never meet,” Vazquez said.

Vazquez also talks about how important it is, especially right now, for benefit shows to take place, not only because of people’s current financial situations, but also their living conditions.

“No matter the size, bigger or smaller, those benefit shows do a lot of good,” Vazquez said. “Especially right now at a time where it seems everything is falling apart and people are losing houses.”

The rebellious and “Do-It-Yourself” spirit and culture of punk rock lives on in the hearts and minds of the bands on stages to the faces in crowds. Southern California is a prime example of this spirit, with a scene burning bright as ever and having plenty of venues and bands to choose from. The scene will continue to evolve and grow along with the people, paving the road for the next generation of SoCal’s punks. In a place where division and separation are anywhere you look, punk stands in defiance as a testament to unity and rebellion.