On the way back home from school, my mother collapsed from exhaustion at the wheel, crashing into the gates of our mobile home park and waking my nine-year old sister with a loud “boom!”

My mother’s accident on the way home from school did more than just total our car– it shattered the illusion of safety that roads in Santa Ana had. According to 2022 data from the California Office of Traffic Safety’s (OTS), Santa Ana ranks as one of Orange County’s most dangerous cities in Orange County: second in DUI arrests, fourth worst for pedestrian safety among seniors, and above average for speeding related accidents. This incident wasn’t just another family tragedy, but a reminder of the dangers that can occur from driving to school.

My now 10-year-old sister, Kenya Jimenez recounts what happened during the crash after she woke up.

“So I think the front exploded, not really exploded, but like, it started working, and [then] it stopped working. Like a boom, smoke came out and then everything else felt squished.” Jimenez said.

“My right side [of] my face felt like a bruise, and then my left did get one,” Jimenez said.

Listening to Jimenez’s childish account of the accident is chilling and something that no parent wants to hear. It makes the reality of driving with your children, especially going to and from school, terrifying and nerve racking.

Jennifer Bersen, mother of junior Landon Cullen illustrates this perfectly.

“…[being] anywhere around schools during AM/PM is a nightmare when cars line up on the street,” Bersen said.

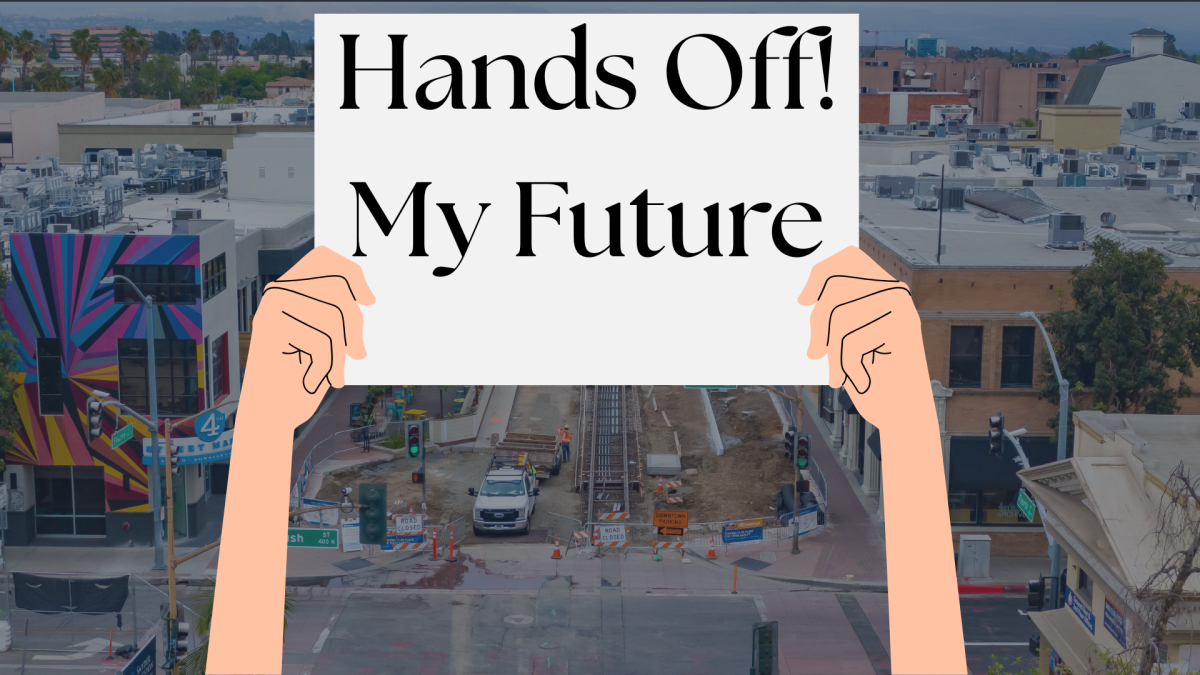

It has become worse for MCHS parents with the ongoing construction on Bristol street.

“If you look at Bristol right out front of the school, I don’t think they’re doing a great job. They’ve blocked off more roads that you could use to get to school; avoid Bristol,” Bersen said.

Bristol Street specifically is known for how bad the traffic can get, with the school having to remind parents about it. As such, there have been many accidents near MCHS. According to UC Berkeley’s Safe Routes to School Crash Map, there have been a total of sixteen bicycle/pedestrian-involved crashes near MCHS from 2023 to 2025. Of those 16, 10 of those have been pedestrians, with one of them being fatal in 2024.

The difficulties of driving in Santa Ana are more pronounced when you’re behind the wheel.

“I tend to feel like I’m panicking most of the time I’m on the road in Santa Ana because there’s so much traffic on all the surface, streets stop and go, and there is construction everywhere. There are pedestrians that run out of nowhere, there’s e-bikes, scooters, razor bikes, motorcycles, regular bicycles, and everything going around. You have to be with your head on the swivel,” Bersen said.

However, the dangers of going to-and-from school aren’t just confined to those driving. For pedestrians, it can be worse, and parents know this.

“I am happily surprised that not more people are hit by cars. Even in crowded, congested places, people are going very fast. And everybody seems like they’re in a hurry to get somewhere. I think it’s dangerous. I feel scared when I’m walking because cars are speeding by and I never know if someone is going to hop the curb and hit me. The people with their loud mufflers [and] revving engines are very mentally challenging as well when trying to walk. The safest thing for pedestrians is when they’re at a crosswalk and there is a button that says you can walk. That’s the safest. Any other time it’s dangerous…” Bersen said.

For parents, they have to worry whether their child will get to school safely as there’s more risks than cars out there. They won’t be there when harm may come to their kid and as a result, some parents require that their children give status updates such as when they got on a bus, when they left the house, when they arrived at school, and more. Each “Ya llegue” text provides a small breath of relief in a routine of worry, showing how a parent’s trust in their child’s safety ends the moment they put a foot out the front door.

The commute to school has become mundane in practice, but in reality, a gamble every time. Families navigate through construction barriers, speeding cars, and unpredictable traffic, all with a slight sense of fear in the back of their minds. The knowledge that a simple trip can end in a loud “boom!” that can shatter more than just glass is a constant in our everyday life. The data points seem normal for a city like Santa Ana, but for parents like Bersen, and children like Kenya, the statistics aren’t just numbers but the memory of a bruise, the sound of a crash, and the new fear that going home isn’t safe anymore.