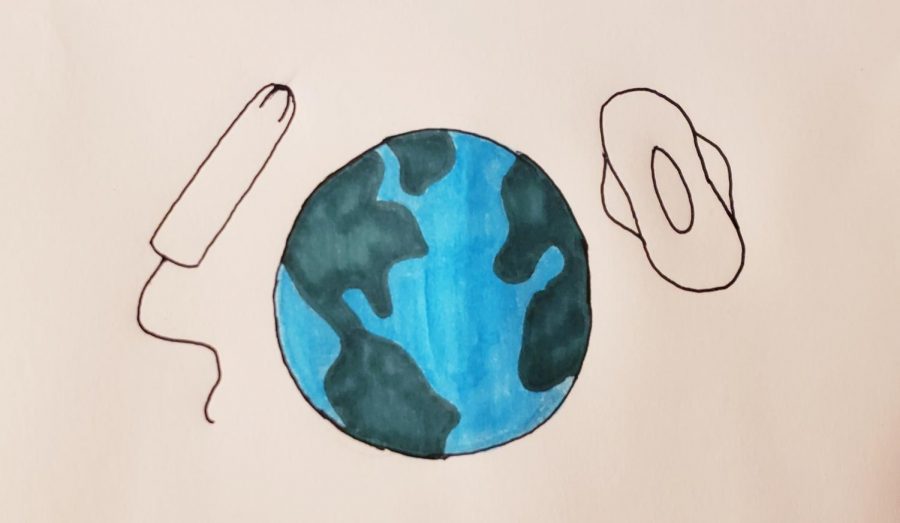

Period discrimination and stigma all over the world

Period products are a privilege that many girls around the world do not get to experience.

Every girl has experienced this: discreetly hiding some cotton product in her sleeve and hurrying to the restroom, trying her hardest to make sure no one knows she experiences the same thing as all the other women in the world. The last thing she wants is to be found out and receive those dirty or confused looks for something so natural. She calls it a “rag,” or “the time of the month,” for she will be deemed vulgar if she calls it what it is: a period.

In other countries, however, it’s not the same. Many girls would not even be able to openly discuss their periods out in the open, even if they used alternative terms. Discrimination doesn’t just come in the form of a social stigma, but also a lack of access. Easy access to menstrual products is a privilege that not all girls around the world get to experience; they result to using old rags that can leak through, or even leaves and sticks. Junior Damaris Carlos said, “I know these girls don’t have it as easy as we do.”

In Nepal, there exists a tradition called chhaupadi, which severely restricts women when they are menstruating. Although it was criminalized in 2017, many women still have to adhere to this. Women are not allowed to touch food, water, or men. They have to sleep in a different room from their family. In the more rural areas of Nepal, chhaupadi experiences its most severe form: women are forced to sleep in huts with cattle, which leaves them vulnerable to severe weather and assaults.

This “impure” mentality isn’t unique to just Nepal. In India, 41.6% of girls do not participate in religious activities during their cycle because of perceived uncleanliness. They’re not allowed to bathe, apply make-up or do anything to upkeep their appearance in order to preserve the balance of their body, as holy texts imply. Exercising and housework are strictly forbidden for the same reasons, too. Like in Nepal, some areas delegate their women to huts during their period.

Kenyan girls, and others living in impoverished African countries, have to miss school for the entirety of their period because of the lack of sanitation and fear of being found out. 32% of schools do not provide a safe and private place for Kenyan girls to change their sanitary pads, should they can even get their hands on them. Menstruation products are so expensive that 1 in 15 had to turn to sex work to afford it. Even in places where access to these products isn’t as much as an issue, girls are taught that their used sanitary products would create toxic waste if mixed with garbage. As a result, they are forced to carry their used products around until they can dispose of them in a proper way.

One reason for this may be religious texts such as, Leviticus 15:19-33, which states that “Whenever a woman has her menstrual period, she will be ceremonially unclean for seven days.” The Quran mentions something of the sorts: “They ask you about menstruation. Say, ‘It is an impurity, so keep away from women during it and do not approach them until they are cleansed…'” In nonsecular countries, these texts are used to justify this treatment of women.

Here in the US, period discrimination is not as severe as it is in other countries, but it nonetheless exists.“I’ve been bullied for accidentally showing a pad I had in my backpack,” said a female MCHS sophomore. “There were times when I stained myself and people would talk about it behind my back, and I was embarrassed.” To girls like her and many others, periods are still something they feel like they have to hide. Even the White House isn’t exempt to this; in a CNN interview, President Donald Trump said that, “You could see there was blood coming out of her eyes. Blood coming out of her wherever,” in regards to Fox News anchor Meghan Kelly. Menstrual discrimination exists everywhere.

Fun Facts:

My favorite Pokémon is Dosclops.

All my clothes are thrifted.

My favorite anime is Mob Psycho 100.