Women’s History Month without the history

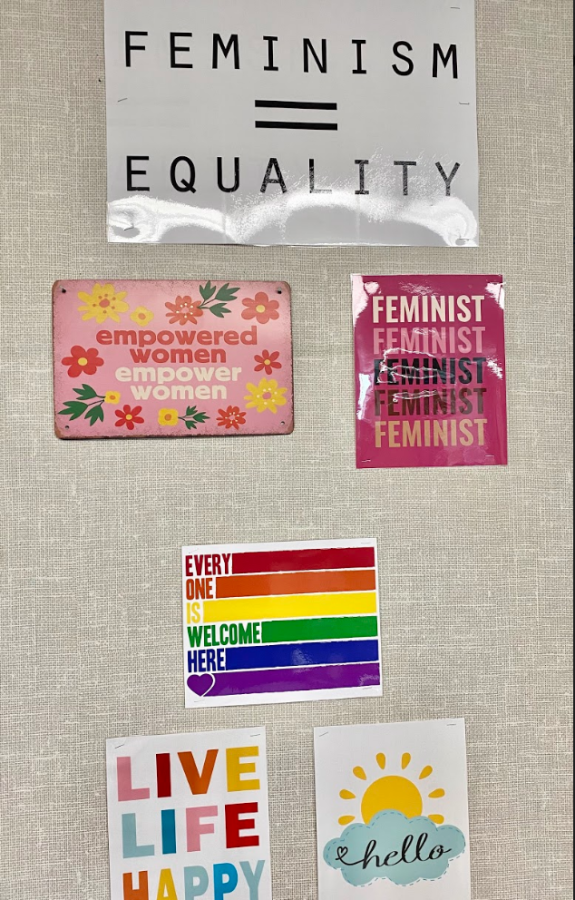

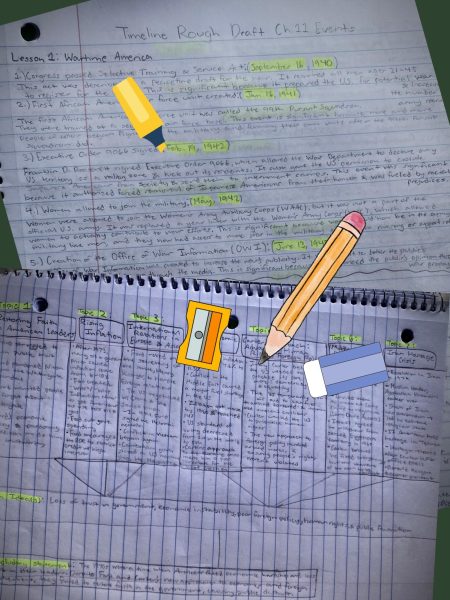

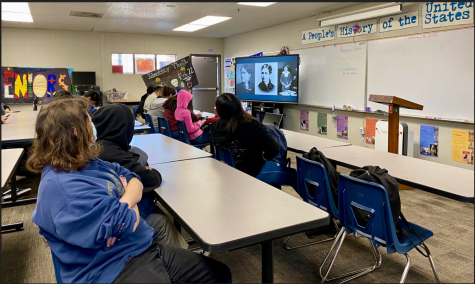

Kathleen Peterson has inspirational posters that she uses to inspire students and bring representation into her classroom.

Rosalind Franklin, Zelda Fitzgerald, Gertrude Bell, Hatshepsut, and Andrée de Jongh were all intelligent and capable women who were pushed at the very back of history books. They are barely acknowledged and instead, were overshadowed by men.

But is it our fault? Most of our understanding and knowledge, especially in history, comes from the education that we receive in school. Does the school curriculum lack information about the contributions of women?

There has always been an absence of female representation in the classrooms and a change needs to be made.

The recognition and celebration of women began as a local celebration in Sonoma, California in 1978. The celebration was initially a week-long event called Women’s History Week which was carried out by the Education Task Force in Santa Rosa, California. The event was very successful; schools planned special curriculum teaching students of women’s contributions to culture, history, and society. The students would then be able to make presentations in the classrooms or even participate in the “Real Woman” essay contest.

Later on, it was declared that March 8, would be International Women’s day. The celebration spread between different cities and in February of 1980, the event was recognized by President Jimmy Carter. Carter later issued the first Presidential Proclamation which officially declared March 8, 1980 as National Women’s History week. Although this was a great accomplishment, each year the date for National Women’s History week changed. This is when the National Women’s History Project, or better known today as National Women’s History Alliance (NWHA), lobbied for the dates to stay the same.

In 1981, Congress passed Public Law 97-28 stating that March 7, 1982 was National Women’s History Week. Not long after, in 1987 a new law was passed: Public Law 100-9, officially declaring National Women’s History Month. Released alongside was Carter’s proclamation.

Since then, the NWHA has been dedicated to providing resources for education, empowerment, equality, and inclusion. Plus, they are the ones who establish a theme each year for National Women’s History Month. In which case, the theme for 2022 is “Women Providing Healing, Promoting Hope”.

Today, Women’s History Month is celebrated in an elaborate way; libraries host events, people go to marches, and March is the recognized month to celebrate women.

Why is it that the contributions of women are included everywhere except in schools? School is a place to learn, why aren’t students being taught about women?

History teacher Rafael Ramos said, “One reason that women are not talked about is because men still have more influence and power than women. This fact impacts all of the decision making in our society, including what will be taught in schools.”

Similarly, English teacher Kathleen Peterson said, “It’s all about the person in power and them not wanting to give up the power.”

Both of them collectively agree to say that men influence the curriculum to continue to glorify them, while continuing to leave out women which creates a disbalance in what students are learning.

UCLA student and MCHS alumnus Andreanela Ordoñez who is majoring in Chicanx Center American Studies and Education Social Transformation said, “It goes back to the system and how things have been designed, like the patriarchy. Due to how the U.S sees ideals, it started to force down and oppress women.”

The lack of female representation in classrooms is noted by students even throughout their educational years.

Freshman Kaekoa Corona said, “I’ve heard of women in school, but in middle school. One of my teachers went over famous women writers and how they’ve contributed to so much of the writing world.”

Why is it that students can only recall information that was presented to them in their earlier years of education?

Even so, the same few women are the only ones students learn about over and over.

“I couldn’t not remember any examples [of historical figures]. Sacagawea is one of the few women represented in the classroom,” said Ordoñez.

While in schools, students can recognize that there is a lack of diversity in the authors and in the materials that they are presented with.

Junior Cecy Rivera has noticed women missing in her history classes.

“When it comes to history, a lot of the things are quoted from men, a lot of the sources are from men,” she said.

The information presented also doesn’t capture women as protagonists.

“In history, women are seen as background characters. That affects us in the long run because there never were women front and center,” Rivera said.

On the other hand, Ordoñez said, “Women are seen in a negative light, like in the witch trials. We hardly talk about the accomplishments in which women have helped throughout history, we talk about them briefly or not a lot. Or it’s misleading.”

Instead of promoting accomplishments, the curriculum focuses on the idea that women didn’t do any meaningful work. Students have also been fed this narrative far too many times.

Junior Susana Giles has also noticed patterns in the information presented in class.

“A lot of things are how women suffered but not the ways in which they contributed.” Not only that, but she said, “Most male teachers don’t want to talk about the topic of women because they are scared of what girls will think.”

The teachers’ lack of knowledge of women’s history or even their unwillingness to discuss women in class takes away the opportunity for young girls to know about women and discuss social issues.

Ramos said, “Teachers signed up to teach and that means that they agreed to possibly have to teach ideas, issues, and topics that maybe they do not agree with and that might make them ‘uncomfortable.’ Also, I don’t see how those topics could possibly make someone feel uncomfortable. The argument that we should not talk, or teach, certain things because it ‘will offend others’ is flawed. If we do not talk about women’s suffrage and their contributions, it is women who we are offending. We are ignoring and erasing their experiences, and the history of their gender. We are saying, ‘you do not matter.’ And that is truly offensive.”

There are also consequences to not being taught about women in the classroom.

Ordoñez said, “It affects students in a mental way that schools don’t even realize. In my experience, it made me believe that I couldn’t be a lot of things. You are basically being told that your community hasn’t contributed to the world because history is being presented through a eurocentric lens. It molded my expectations and values.”

Ramos summarizes this idea.

“When the curriculum does not reflect you and your identity, it sends the message that people like you do not matter, that you are not important, that there is no place for you in this society, etc. And that can definitely lead to psychological and self-esteem issues. It can really impact your ability to build confidence. It may also lead kids to have no interest in the curriculum, or they may not take it as seriously, because it does not reflect their experiences and lives.”

Ordoñez said, “You can’t be what you can’t see.”

If there is no representation then how can female students dream about becoming a leader, advocate, pilot, lawyer, or any other male dominated role if they have not seen women in those roles.

It has already been established that there is an absence in the curriculum, but how can schools be more inclusive?

Ordoñez said, “First of all, schools can acknowledge that our history has a place in the classroom, it shouldn’t be a novelty.”

Women make up about half the population, women have been here just as long as men, women are not a novelty and should be freely discussed, just as men are talked about in class.

Ramos said, “It is everyone’s responsibility to teach about the contributions of women. You can do it in any subject. An English teacher can select books that talk about womens’ issues and what it means to be a woman.”

Oftentimes, educators must take on the responsibility to educate students, they are the people that students look up to for their education, and that education should be a well rounded representation of women whether directly or indirectly.

Instead of only focusing on Women’s History Month in March, teacher and Ladies First adviser Kathleen Peterson tries to implement pieces of inspiration and women empowerment through her classroom all year round.

“Students try to talk about what isn’t talked about, students make up for what the school system doesn’t teach them,” said Rivera.

Ladies First is run by president and junior Jennifer Lopez and vice president and junior Susana Giles.

“We are a feminist group. We spread awareness, we get information that we learn and teach it. We reach topics that aren’t talked about anywhere, either at home or other places. For our club, we are the source of information, we are the source for other female students,” said Lopez.

Women are not being talked about enough in schools and in the classroom, there needs to be change and although students can take the initiative to promote for studies that they would like to learn about, the whole curriculum and the perspective of educators need to change. Female students need to be able to feel that they are acknowledged, and male students can learn about women’s history.