What’s wrong with the lead contamination in Santa Ana?

In the heart of Santa Ana, a hidden danger silently flows through the soil, affecting the city’s most vulnerable communities. A lead contamination crisis has emerged with low income neighborhoods facing the force of a century old problem. Despite evidence of severe health risks, state regulations have left children at the mercy of unregulated lead exposure. Finally the unraveling of this crisis is finally being revealed, exploring the research efforts of Orange County Environmental Justice (OCEJ) and the University of California, Irvine’s Public Health Department, bringing light on the consequences and advocating for policies that could protect Santa Ana’s future.

The seriousness of this issue isn’t talked about as much as it needs to, according to the article “PloNo Santa Ana! – Background” written by Orange County Environmental Justice (OCEJ). They explain the significance of the matter and how this issue is being ignored even though it’s a serious problem.

OCEJ members wrote, “According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 400 parts per million (ppm) is defined as soil lead hazard in areas where children are present. However, the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment has deemed that level too dangerous for children, and therefore lowered its soil lead risk standard to 80 ppm in 2009. Despite having evidence to prove such consequences, the state fails to set the 80 ppm a state regulation. Furthermore, the state does not adequately enforce lead testing in children and much less monitor the situation, leaving low-income brown children at high risk of unregulated lead exposure and poisoning.”

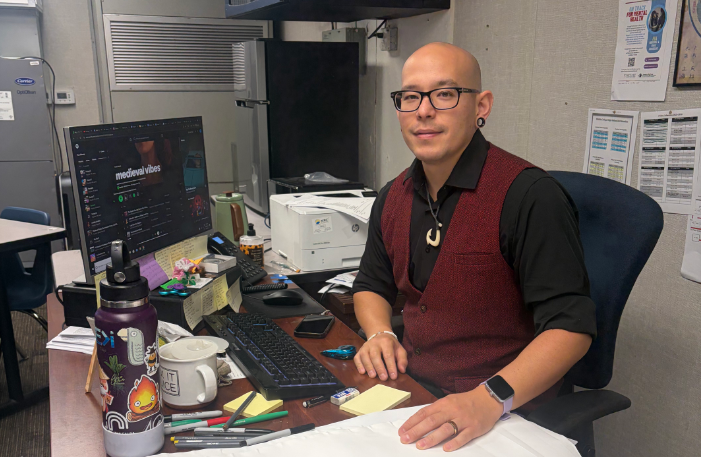

Maya Cheav, director at OCEJ, speaks about approaches to remediation, including the use of seed pods to naturally absorb lead from the soil. Cheav later shares a presentation where OCEJ visits Lathrop Middle School to make these seed pods, Bioremediation + Seed Balls.

“Mediating soil is a method to get rid of lead. We use a method called ‘dig and duck’—moving it is labor-intensive and has to be done safely. Another method we’re exploring is using seed pods, which is cheaper and is a natural ecosystem solution. It’s called ‘bioremediation’,” Cheav said.

You may be wondering how is this such a problem? Cheav brings to light the challenges posed by lead contamination, historical sources that still contribute to the problem, and the ongoing struggle to enforce necessary needs.

Cheav goes on to explain the urgent need for community awareness, prevention strategies, and regular blood lead testing for affected children.

“Lead poisoning is not natural in humans. There’s no safe level. Health effects include anemia, asthma, learning disabilities, and speech problems,” Cheav said.

Jun Wu, co-director of the UCI Center for Environmental Health Disparities Research, explains the many different factors on why the lead contamination issue has taken longer for the city of Santa Ana to fix, ranging from old house paint to communities being poorer due to the lack of resources.

“The lead contamination issue has taken longer to be addressed because of multiple reasons; one historical source is still posing risk nowadays, for example the paint from older houses produces lead in the soil due to historical traffic emissions. Two leads will stay in the environment for a very long time. Three poorer communities may be facing higher lead contamination due to older communities, the lack of resources to clean, and the lack of awareness,” Wu said.

Additionally, Wu shares how the issue is more common in older communities that are more outdated and more run down, which would most likely be in the less wealthy areas of Santa Ana.

“Older communities with older houses, in proximity to freeways/arterial roads and historical traffic, older pipes etc. Low SES communities,” Wu said.

Wu tells us that the reasoning on them receiving the $2.7 million dollar grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences has to do with the academic issues with lead exposure, especially in children.

“There is a lack of study on understanding the relatively low-level of lead exposure (compared to decades ago) on children’s neurodevelopmental outcomes and school performance. Community-driven questions will be addressed by the strong community and academic collaboration. This is an action oriented research project,” Wu said

The article Final Strategy to Reduce Lead Exposures and Disparities in U.S. Communities highlights the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) combined effort to destroy lead exposure within American communities. It goes into the details on the severe health risks that come along with lead exposure, particularly in children, and the ongoing downfalls along racial, and ethnic lines. Along with the priorities of the Biden Harris Administration, the strategy aims to promote environmental justice and support underserved communities by giving resources for lead pipe replacement and paint removal. With four main goals and three approaches, the EPA seeks to reduce lead exposures locally, nationally, and through collaborative efforts with many stakeholders. The strategy’s development has to do with engagement with the public, including listening sessions and feedback collection, to have inclusivity and consideration of diverse perspectives. Finally, the strategy includes plans for tracking progress to guide communication efforts, highlighting the EPA’s commitment to addressing lead exposure as an important public health concern.

The Santa Ana’s lead contamination crisis, highlighted by the efforts of organizations like Orange County Environmental Justice (OCEJ) and the University of California, Irvine’s Public Health Department, highlights the urgent need for action.

Ignoring decades of neglect, the consequences of lead exposure continue to reach out, affecting vulnerable communities, including children, who face severe health risks such as anemia, asthma, and learning disabilities. The lack of regulation and enforcement worsen the situation, leaving children at risk of unregulated lead exposure.

Research by Jun Wu shows us the hard factors adding to this crisis, including historical sources. The grant’s meaning shows us the urgency of addressing lead exposure’s impact on children’s academic improvement.

The showing of Santa Ana’s lead contamination crisis acts as a call for change to help the health and academics of future generations, academic research, and shared efforts to give a leadless future for Santa Ana.